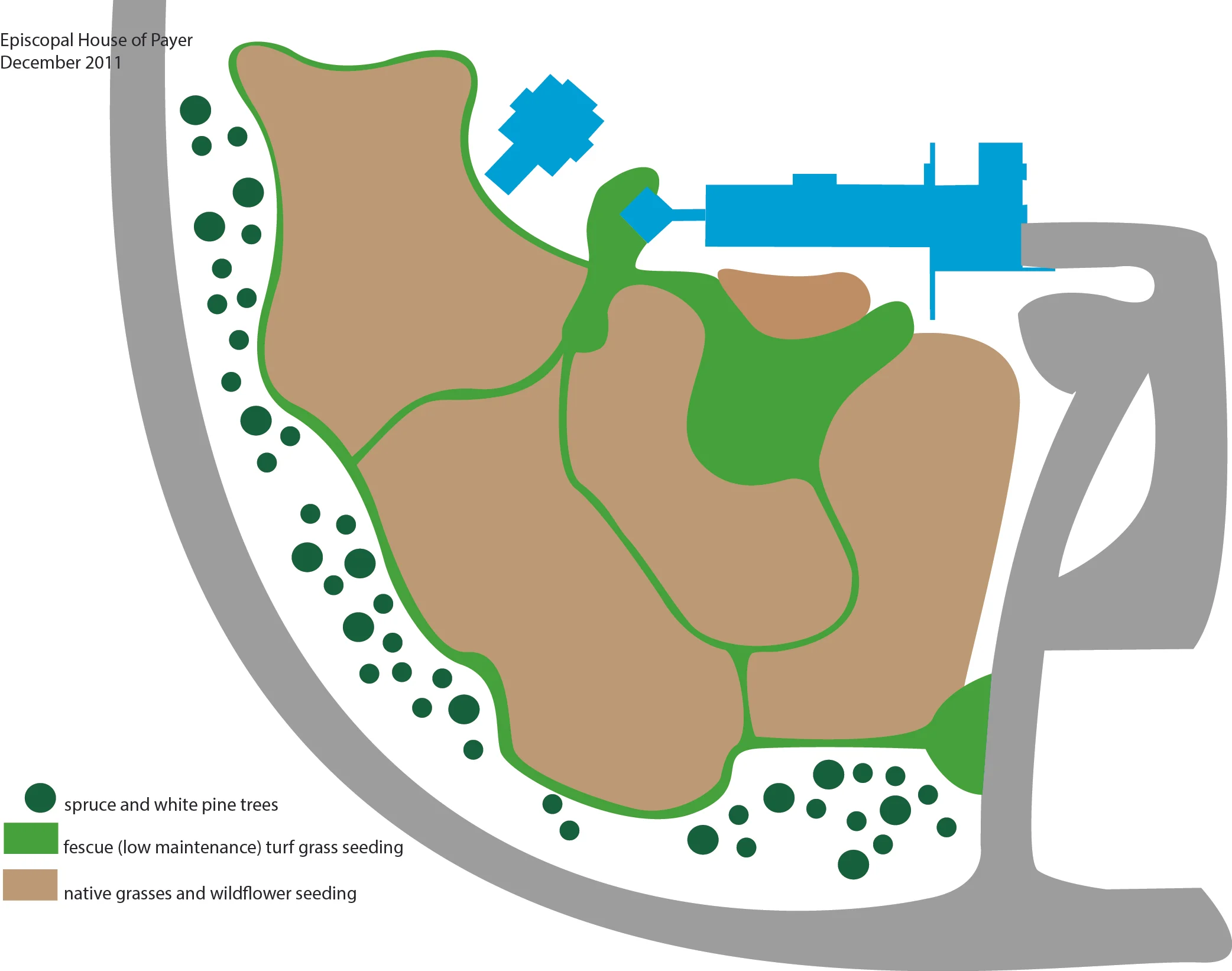

This design was for the Episcopal House of Prayer on the edge of the Saint John's Abbey property. The green represents areas that we seeded in fescue--a low maintenance turf grass--that made up the paths and several open spaces, and the brown represents areas that we seeded in native grasses and wildflowers. Illustration by Steve Heymans.

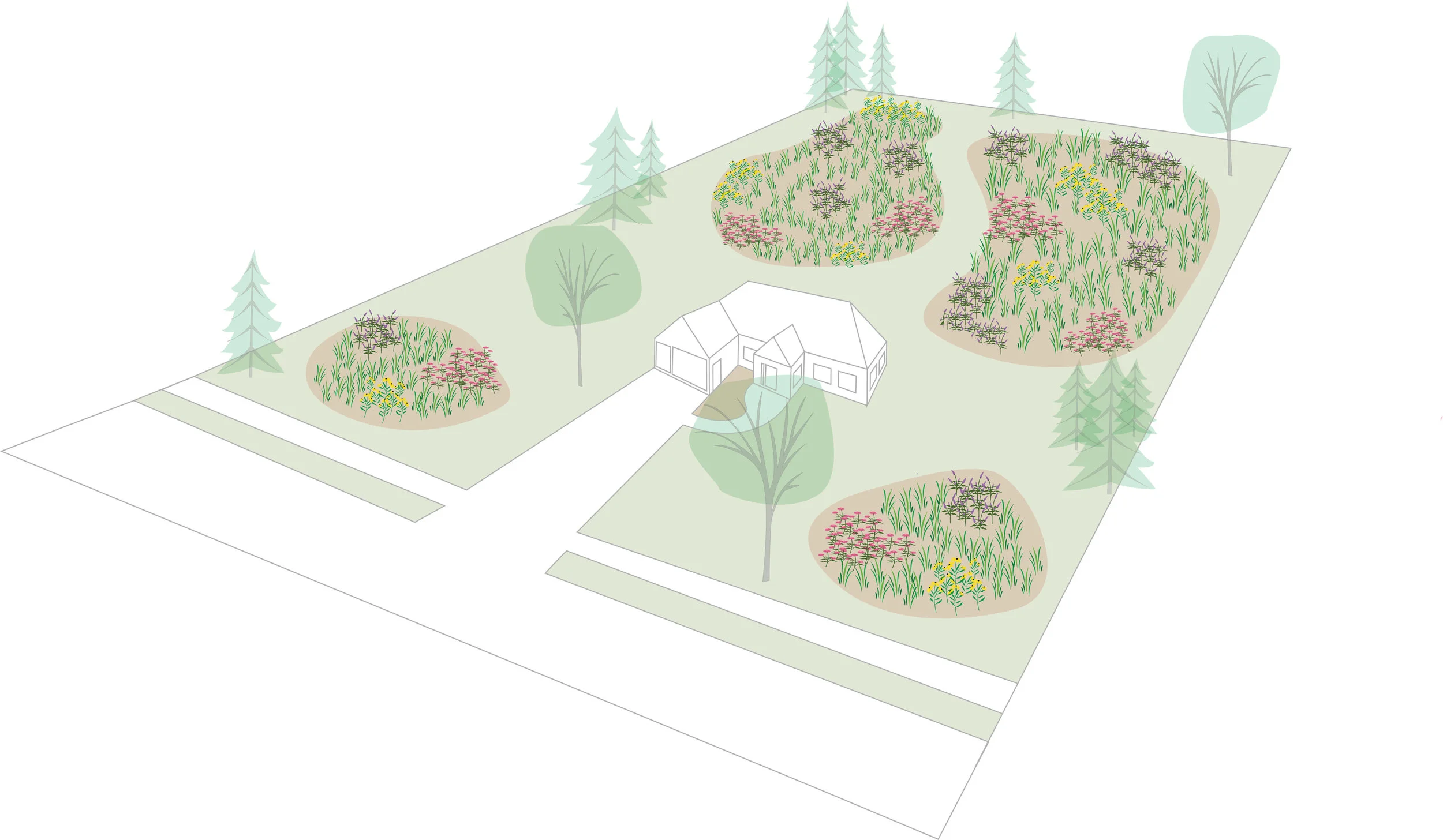

Most turf grasses are high maintenance--requiring watering, fertilizing, herbicides, and mowing. Despite this, most yards are seeded with turf grass. Prairie, or pollinator, plots give us a wonderful alternative to the exclusively turf grass landscape. Illustration by Steve Heymans.

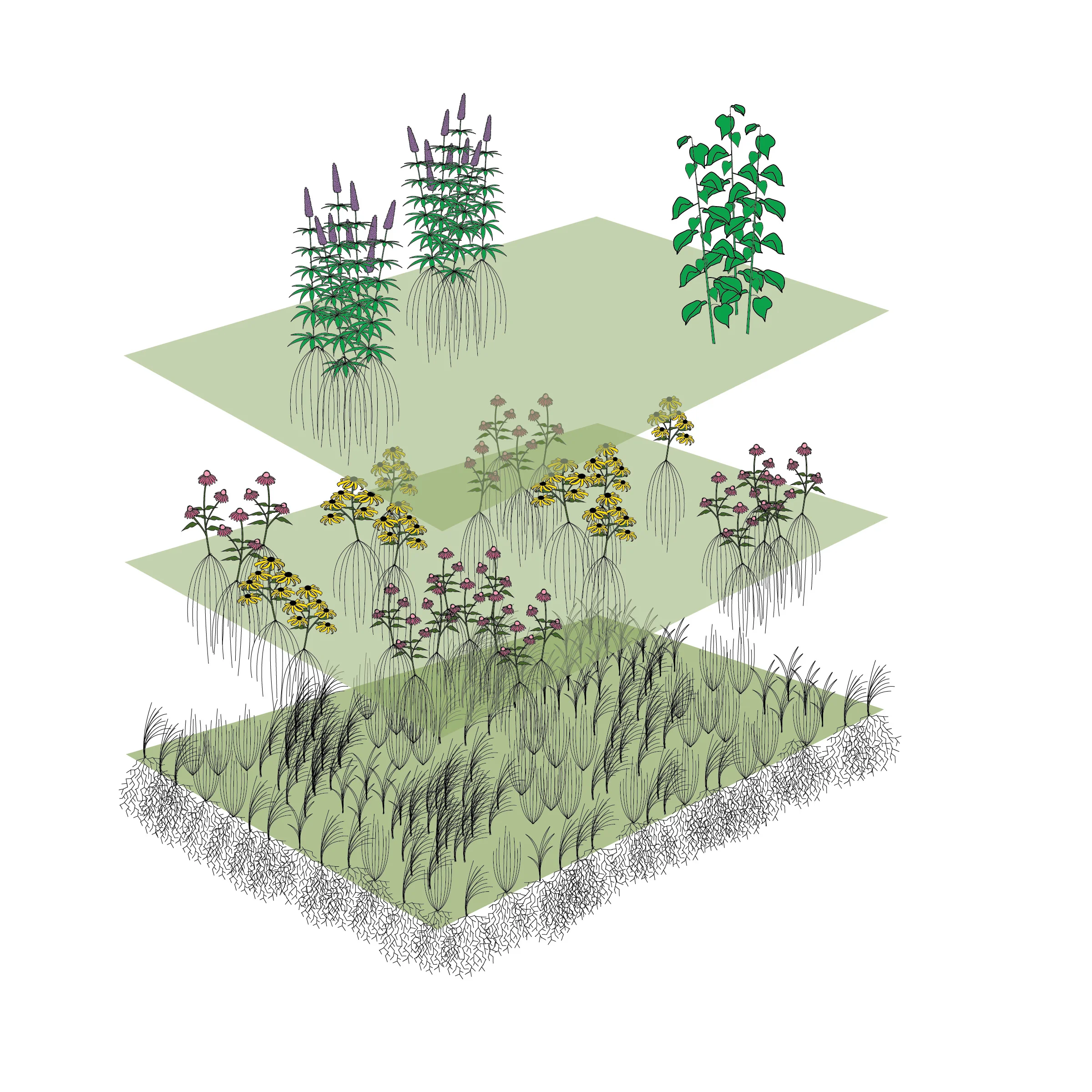

Our three-layered approach involves native grass seed on the bottom layer, wildflower plugs on the second, and more structural plants (often potted) on the third, or top, layer. Illustration by Steve Heymans.

Seeding prairies requires specialized equipment, such as no-till drill seeders. We use the Kasco Eco Drill for smaller, lower, and wetter projects (see above), and a Great Planes no-till drill for CRP seeding and larger projects.

Prairies

A good way to learn about a prairie-scape is to see how one is created. What follows is a brief description of this process.

Step One: Design

There are several elements of design involved in creating a prairie-scape. We focus on access/engagement and plant communities that are optimal for the property's conditions.

Prairies are not meant to be merely viewed like an artifact in a museum. They are meant to be engaged. But first one must be able to access them. Paths and green spaces are a very important element when designing a prairie.

Paths afford us an adventure, anticipating what awaits us at the next bend. Paths are whimsical in that they appear to have come about not by a grand design but by accident. But they also invite mobility—space is meant to be traversed.

Paths also end up framing plots, in this case our plant plots. This framing is what allows a landscape to look like it belongs; it is intentional as opposed to appearing unkempt. Prairies are natural and wild, and the framing afforded by a mowed grass path frames it in the way a picture frame contains a painting of the Alaskan wilderness. Context says as much as content.

Paths also function for managing a prairie plot in that they serve as firebreaks—areas over which fires will not traverse—when burning a prairie, which is recommended every few years when possible.

It is this back and forth—natural and cultivated, prairie and turf grass—that contributes to a successful design.

Paths and plots also work together to create movement through what is otherwise a rectangular property. Such movement is what we see in nature, which rarely generates straight lines. Such movement is what piques our curiosity as to what is around the bend or over the next knoll.

Seed or Plugs?

One reason that prairie-scapes are surprisingly affordable is that most of our prairies are created with seed. And of course seed is less expensive than buying and planting plants. But we also start some plots with plugs—very small plants grown in containers that we simply “plug” into the ground.

Sometimes we employ a combination of seed and plugs by creating a foundation of native grass seed and then plugging in flowers after that. This allows us more design control over the final outcome of the prairie.

The Three-Layer Approach

In each case, whether by seed, plugs, or a combination, we think of a prairie plot in terms of layers: the ground cover layer, the seasonal floral layer, and the structural layer.

The ground cover layer is almost always made up of seed, because we blanket the whole plot with it. Design-wise it serves as a matrix, a base, or foundation upon which everything else rests. It is the background, as it were, upon which all else is highlighted. Functionally, it provides ground cover so that there are no empty spaces in which weeds might gain a foothold.

Upon that we design the seasonal layer, selecting wildflowers that bloom at various times throughout the growing season to ensure that there are always plants in bloom. For example, Golden Alexanders, Lupines, and Beardtongue are some of the few native flowers that bloom in early spring. From there the parade progresses right up to the end of fall with the blooming of the asters and goldenrod.

The third layer of a prairie plot we call the “structural layer,” by which we mean larger plants that stand out such as an Eastern Red Cedar, Veronica, Maximillian Sunflower, Cup Plant, or the Grey-headed Coneflower.

Step Two: Installing a Prairie

Perhaps the most important rule for installing prairie is to get rid of the existing non-native plants (such as weeds or turf) while disrupting the soil as little as possible. This usually means the application of Glyphosate, the active ingredient in RoundUp. While we would prefer not to use any herbicides, Glyphosate is, as far as we know, the least harmful to humans and insects. Its virtue is that it kills a plant through its foliage, not through its root system (which gets into the ground and water supply).

Without herbicides, we would have to kill the existing vegetation by tilling. But tilling the soil animates weed seeds that have been lying dormant for decades waiting to germinate. To work the weed seeds out of the soil takes years, a time frame and expense few are willing to endure.

After a season of spraying the future prairie plot, we seed the plot with natives, install plugs, or employ a combination of both. Getting seed in the soil while disturbing it as little as possible requires a host of tools and experience. Determining the methods varies from plot to plot, condition to condition, and is as much an art as a science. As landscapers who focus almost exclusively on prairie and other natural landscapes, Prairiescapes has the tools and experience to install these landscapes.

If we seed in the spring, the prairie will have to be mowed two or three times in the first year. We do this to keep the weeds down and allow sunlight to access the natives, which will not grow much above ground. In the first year, natives are putting their energy in establishing their roots. The next year there will be a good show of certain flowers. By the third year, grasses will be quite visible and a wide variety of flowers can be enjoyed.